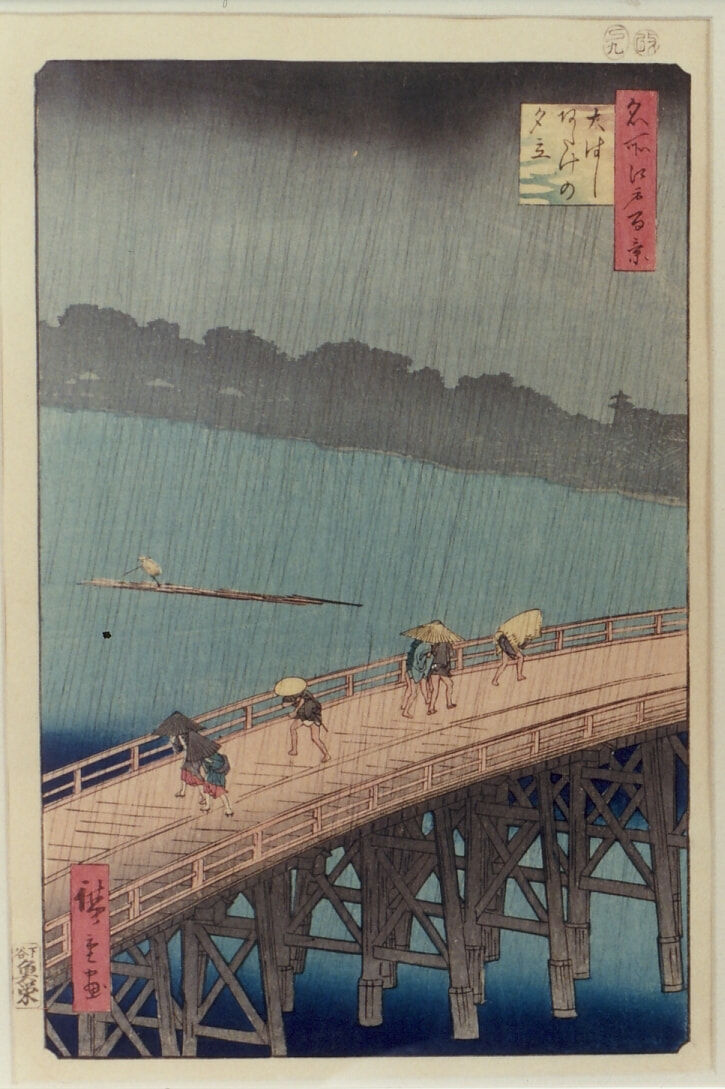

UTAGAWA HIROSHIGE: Sudden shower over Shin-Ohashi bridge and Atake

UTAGAWA HIROSHIGE: Sudden shower over Shin-Ohashi bridge and Atake

By Christine Newcombe

Guides who showed visitors through The Johnston Collection when it was rearranged by Akira Isogawa last year would have noticed this Japanese woodblock print placed casually on the library table in the Dressing Room but, like me, may not have had much to say about it. Yet several people who came on my tours recognised the print and piqued my interest in it.

The print is one of a series by Hiroshige called One Hundred Views of Edo (an earlier name for Tokyo) which was produced from 1857-59. It is considered to be the undisputed masterpiece of the series. It depicts black clouds bursting into sheets of heavy rain, scattering the huddled people on the bridge spanning the Sumida River. A solitary boatman poles his log raft downstream past the area known as Atake. The print so impressed Vincent van Gogh that he did his own version of it in oil, The Bridge in the Rain.

Ukiyo-e, or woodblock printing, originated in China but was greatly improved by the Japanese due to the skill of the craftsmen and the use of washi paper, which can absorb colour and withstand repeated printing. The first ukiyo-e prints in the 17th century were simple monochrome black, but full colour prints were developed by the mid 18th century.

Making woodblock prints was a collective effort involving drawers, carvers, publishers and printers, supported by a host of skilled craftsmen producing the equipment needed for the process, which is as follows: An artist makes a design with brush and ink lines on transparent paper, indicating the required colours. Separate woodblocks (made of cherry wood) are carved for each colour, sometimes taking the carver months to complete. Coloured ink and glue is applied to a block with a brush. The cartoon of the print is applied to the block and a balen (pad) is used to press the paper to the block. These steps are repeated until all the colours are applied. The first prints are usually the best.

The word ukiyo-e means “pictures of the floating world”. This form of art was created for the contemporary masses and depicted images of urban life and natural scenes that ordinary people could relate to. Many early ukiyo-e prints functioned as sex manuals for brides and courtesans, depicting erotic scenes pertaining to the red-light districts of Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. They were mass produced and regarded as disposable in Japan but were highly collectable in the West. Claude Monet and Frank Lloyd Wright were two notable collectors.

Hiroshige (1797-1858) is regarded as one of the great landscape artists due to his unique style of intimate, small scale works of famous places which were often inspired by his own travels. He was famous for his unusual perspectives, seasonal allusions and striking colours. Hiroshige started life as a low-ranked Samurai, an hereditary retainer of the shogun. In particular, he was an official within the fire fighting organization whose duty it was to protect Edo Castle from fire. His duties gave him time to draw and study art. According to legend, Hiroshige was inspired to become an artist by Hokusai, his contemporary, whose image of the Great Wave is one of the most famous graphic images in the world. Eventually, Hiroshige passed on his official occupation to his son and pursued his art. In 1856, Hiroshige retired from the world and became a Buddhist monk. This was the same year that he began his One Hundred Views of Edo. It was published posthumously and was immensely popular. He died aged sixty-two during the great Edo cholera epidemic, and is now regarded as the last great ukiyo-e artist.

This article was originally published in fairhall, Issue 3, July 2011, pp 14.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter