THE TEA TOWEL

THE TEA TOWEL

By Irene Villis

What type of tea towel do you like to use in your kitchen? Pure Linen? Cotton? Expensive?

Even Queen Elizabeth II takes the time to choose her own. Journalists have frequently reported how the Queen likes to be hands-on in an informal setting. It is said that Prince Phillip likes to work the barbecue, while she makes a point of doing the washing up. In 1976, the former British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, during a visit to the Royal Balmoral estate in Scotland is said to have broken the news of his resignation to the Queen whilst she was washing the dishes.

Tea towels or tea cloths (UK English), originated in the 18th century as an accessory for the upper class. Technically a tea towel is a large piece of cloth, usually made from linen or cotton that is intended specifically for drying dishes and cutlery. Historically, they were meant for use in tea service and traditionally they were found in England and Ireland, where tea was and remains a daily ritual.

Listed in the Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities 1550-1820, a tea cloth was a small cloth made of linen to fit a “tea table” or “tea tray”, and the Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest date of use in this sense is 1770. Tea towels came later in the latter half of 18th century and originated in Britain. They were referred to as a ‘drying up cloth’ and were made from soft, lint-free linen or fibre derived from the flax of linseed plants Linum usitatissimum. The linen texture of the fabric was prized for its softness, was stronger when wet than dry, and had a smooth surface, making the final fabric lint free. It was a versatile and absorbing tool for the lady of the household to dry her expensive bone china, delicate tea sets and fragile glassware as they were too precious to allow their servants to dry them.

Housekeepers guarded and kept inventory of the linen closet. The right cloth for the right job was a must. In 1803 the linen inventory of Trentham Hall in Staffordshire, England, listed 189 domestic cloths: china cloths, pocket cloths, glass cloths, lamp cloths, dusters, horn cloths for polishing beer cups in the servants’ hall, to name a few. Cleanliness was powerfully associated with gentility. At the turn of the 17th century one of the most productive in an economic sense was the making up and maintenance of personal and household linen. Gentry women would oversee their female servants spin textile fibres into yarn and then contract local weavers to transform that yarn into cloth. By the second half of the 18th century however, gentlewomen were responsible for purchasing cloth and once bought, processing it. Sheets, pillowcases, towels and napkins for family and servants were all cut, stitched and labelled.

The linen cloth during the 18th century was frequently embroidered to match the table linen. It was a way for ladies to show off their embroidery skills. They were often gifted to friends and family, stitched with flowers, initials, or creating heirlooms to be passed down generation after generation. They came in handy during tea service for a variety of uses; they were wrapped around tea pots for insulation, they kept one’s hand from being burned by the pot handle when serving the tea and prevented drips when pouring. Just before serving tea they were also draped over a plate of freshly baked pastries.

The term tea towel however, originated in the 19th century and by that stage to the early to mid-20th century, a glass towel or tea towel would have been a striped or checked cloth. During the Industrial Revolution and the 19th century the tea towel became a more widely available consumer item, and manufacturers turned to durable fibres such as cotton.

Early 20th century household manuals sometimes call them glass towels or, just, towels. Some use terms such as “damask towelling” to explain the patterning and “crash towelling” to indicate the grade of linen used. “Crash” being a plain, coarse, loose weave made from uneven yarns originally woven of linen, jute or hemp.

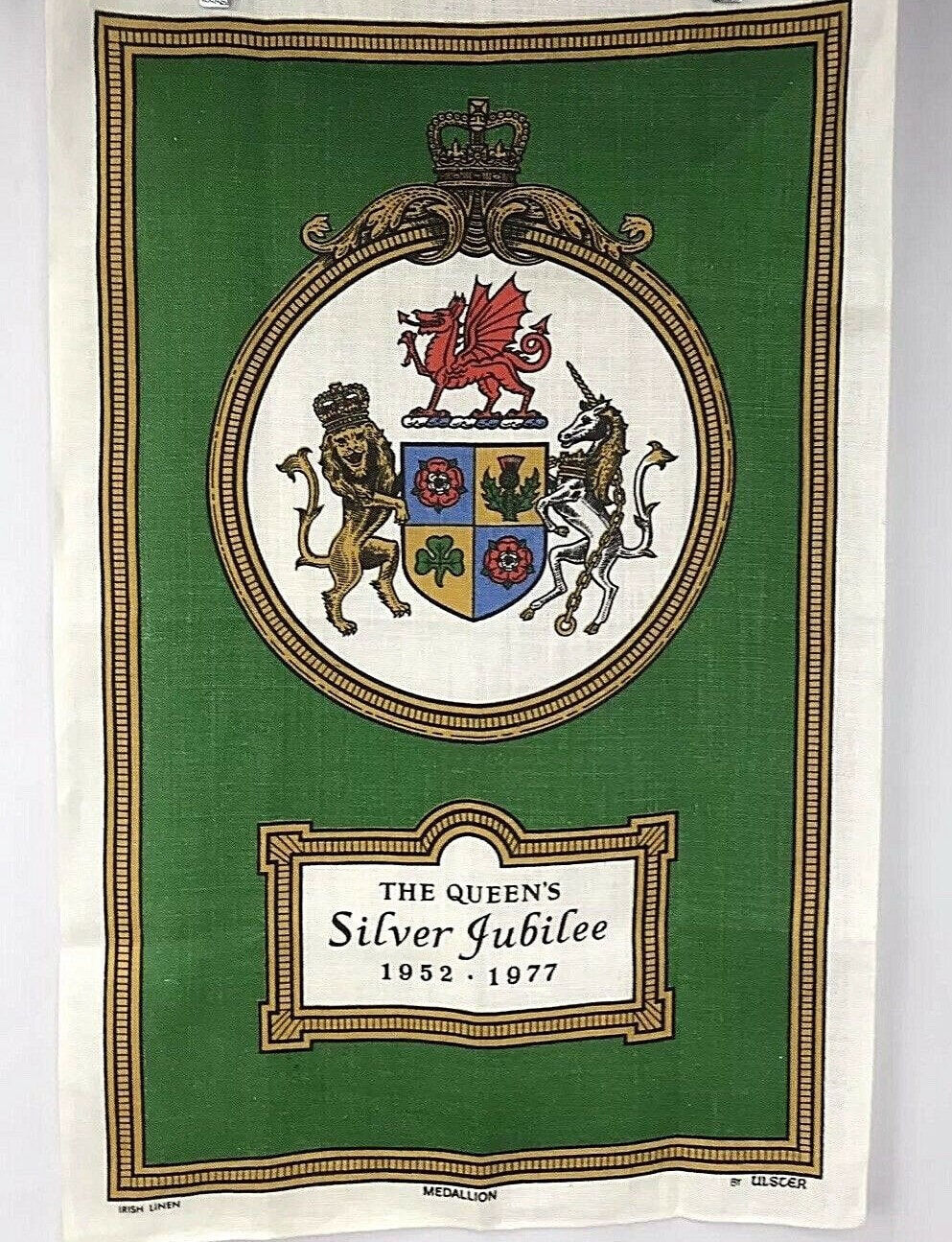

The first commercially successful printed tea towels were pioneered during the 1950s. Artists and designers have since used them as a vehicle to disseminate their work to a wider audience. These days a chosen tea towel may carry a meaningful sentiment, purchased as a memento, a souvenir from a museum or destination, as a commemorative piece or even political statement. The prized tea towel whilst still useful has also become a styling accessory in our contemporary kitchens.

This article was originally published in fairhall, issue 29, March 2020, pp 23.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter