THE HAT: FRIVOLOUS ACCESSORY, OR NECESSITY?

THE HAT: FRIVOLOUS ACCESSORY, OR NECESSITY?

By Jan Heale

Whether it be merely a device to ward off cold or a delectable concoction of feathers and flowers, it is the skill and inventiveness of the Milliner that can turn a simple hat into a wearable work of art.

The term ‘milliner’ was first used in about 1530, when the fine fabric and straw hats made in Milan became known as ‘Millayne’ bonnets. In the 17th century milliners were predominantly male, but from the beginning of the 18th century millinery became a largely female occupation.

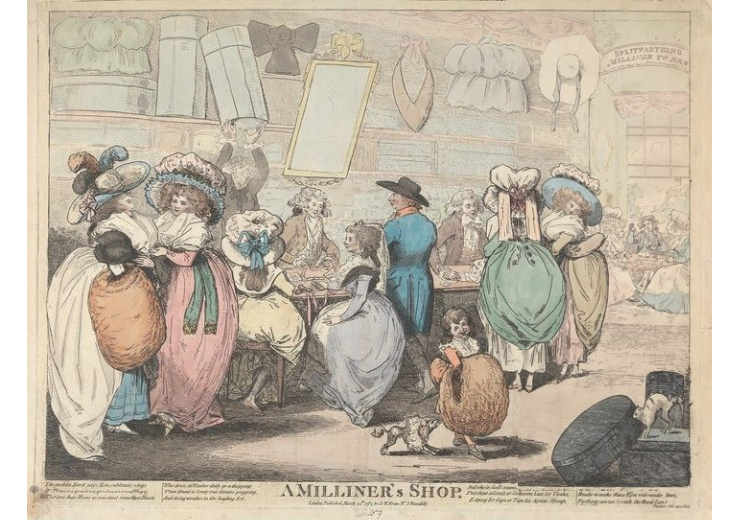

The mantua maker, the haberdasher and the draper, worked alongside each other, while the milliner crossed the boundaries between them. The milliner not only made the hats and bonnets to go with costumes, but also chose the lace, buttons, trims and accessories, to go with the entire ensemble. The millinery shop also sold stays, fans, gloves, parasols and other desirable items of female attire. One alternative (but incorrect) explanation offered for the use of the term ‘milliner’, is that it was because the shop stocked a thousand (or million) things. In 1747 The London Tradesman described a milliner “as a retailer who would furnish everything to the ladies than can contribute to set off their beauty, increase their vanity or render them ridiculous”.

For those wishing to be dressed a la mode, shopping was a serious undertaking, whether done in person or by proxy. Wealthy upper-class clients were favoured with visits at home, whilst provincial customers were able to take advantage of a mail order service. One advertisement promised that the customer’s “wishes and tastes” would be attended to “precisely as if they were present in London ...”. Hats have forever been subject to the vagaries of climate, fashion and society. Jane Austen’s letter to her sister Cassandra in 1799, described her preparations for a January ball, where she is to wear a borrowed “mamalone (Mamolouc) cap”, that is “all the fashion now; worn at the opera and by Lady Mildmays …” She also undertook to buy some trims for her sister whilst in Bath, noting that ‘‘Flowers are very much worn, and Fruit is still more the thing”. However, she thinks “it seems more natural to have flowers growing out of the head than fruit”. In 1811 she acquired a new bonnet, but “now nothing can satisfy me but I must have a straw hat, of the riding-hat shape like Mrs Tilson’s; and a young woman in this neighbourhood is making me one”. Bonnets were popular in the first half of the 19th century which also saw the introduction of the Bavolette – a ribbon frill at the back of the bonnet to cover the neck, which in the Victorian era was considered to be an erogenous zone.

Popular novels and much of the literature, cast the millinery shop as a stage on which a male customer might hope to seduce a young female worker. One 18th century observer claimed that “The Resort of Young Beaux and Rakes to milliners’ shops exposes young Creatures to Many Temptations”. Further, that “a Young Coxcomb … Master of an Estate and small Store of Brains effects to deal with the most noted Milliner” where the “Mistress tho’ honest, is obliged to bear with the Wretch’s Ribaldry out of regard for his Custom”.

Rather than millinery being suitable only for girls from the poorer classes who needed to work for a living, historical records show that many daughters from the gentry and professional class, had fees paid by a parent to be formally apprenticed as a milliner. Once qualified and setting up as Mistress in business for themselves, they could make a good living providing fashionable items to upper-class clients.

One such young lady was Eleanor Mosley, the daughter of a well-to-do York apothecary, who was apprenticed to George Tyler and his wife Lucy in 1718. George Tyler was a freeman registered under the auspices of The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. Lucy Tyler was never identified as a milliner by the Clockmakers, ten percent of whose members followed other trades, but the benefits of Company membership were passed on from husbands to wives. In 1727 Eleanor Mosely earned the freedom of the Clockmakers Company in her own right. Two year later she established herself as Mistress of a millinery business in Gracechurch Street, London, where she now employed apprentices of her own.

This article was first published in fairhall , Issue 15, July 2015, pp 16.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter