WASH YOUR HANDS WITH SOAP

WASH YOUR HANDS WITH SOAP

By Irene Villis

As the world faces yet another pandemic, countless archaeological and historical records show that people have lived with infectious diseases for thousands of years.

Germs or infectious microorganisms such as viruses and bacteria have shaped civilisations and have changed the communities they have spread through. The rate, scale and exchange of disease increased dramatically during the 16th century with the merging of the Old and New Worlds. Dreaded epidemics like the plague, cholera, yellow fever and smallpox appeared unexpectedly and spread quickly across the globe. We witnessed then as we do now, different parts of the world at different times experience their own versions and reactions to disease and epidemics.

During the Georgian era as antiquarians and medical scientists mapped the medical past, many physicians were very interested in epidemic diseases. There was a belief that disease was spread by miasma (from unhealthy or poisonous smells in the air, coming from rotting matter such as vegetation, sewage or corpses). This led to changes in public health practises that significantly reduced the risk of infectious disease with the removing of garbage, cleaning of streets and purification of water. However, the connection between uncleanliness and the spread of diseases was not properly understood and state–mandated hygiene and preventative measures against them were still alien.

The observation of 18th century epidemiology was acquired from the writings of physicians such as Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689). He was known as the English Hippocrates with his insistence on careful examination and follow–up of the patient. He taught that more could be learned about disease from studying the patient than from books. He researched the prevalent London epidemic diseases of the time such as smallpox and fevers and recognised that these tended to occur in particular localities and in particular seasons. His scientific attempt to classify diseases was invaluable – an early stage in what was to become the important science of vital statistics. His detailed books were reprinted and translated throughout the 18th century.

England’s rapid population growth during the 1700s led to overcrowding, poverty and a lack of sanitary living. Crowded urban environments, including affluent households saw the spread of flea and rat infestations. Diseases became rampant and people died as a consequence of poor hygiene. Medical knowledge was basic and healthcare improvements were gradual. Surgery was dangerous as unsterilised surgical instruments caused wounds to become infected. Infection killed many women in childbirth and even having your tooth pulled could prove fatal. To see a physician was costly, the poor were often left to seek alternative help from apothecaries, barber–surgeons, midwives, or even quacks who offered various (often useless) powders and elixirs for pain relief.

Between 1700 and 1830, endemic infections, like smallpox and the fevers, were common in London. Medical responses to illness centred on the individual patient. It didn’t extend from the individual to the impact on society at large. Many physicians who were interested in epidemic disease established beneficial medical topographies and kept their own records. These included causes and cures, data from hospitals, dispensaries and Bills of Mortality. As connections with specific diseases and insanitary conditions were found, doctors sought to make the individual’s environment healthier through public health and education, dispensaries and hospitals.

Through the philanthropic ethos of the time a series of hospitals were built between 1720–1745. There were five general hospitals as well as the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and Queen Charlotte’s maternity hospital in London, but admission to the general hospitals failed to meet the city’s social and medical needs. As concern with one of London’s biggest killers, smallpox, and other infectious fevers rose, new methods of tackling the problem were developed. The London Smallpox Hospital (established in 1746) and later the London Fever Hospital (established in 1801) specifically intended to remove clusters of infection from the community, as well as playing an environmental role in disinfecting and fumigating infected poor.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762) pioneered the use of smallpox inoculation into Britain from Turkey around 1720. The process called variolation involved injecting the disease into healthy patients with the aim of producing a mild attack in order to build natural immunities. She had this performed on her young son, later her daughter and eventually convinced royalty to be inoculated. This highly dangerous method was improved later in the century when, in 1796, Edward Jenner (1749–1823) introduced the smallpox vaccination with the use of cowpox (vaccinia; a rather rare disease of the udders of cows, transmittable to humans and not severe). This less hazardous process of immunisation was called scarification. The smallpox vaccination was one of the first large–scale public health initiatives implemented in England and by 1980 it became the first major disease to be globally eradicated.

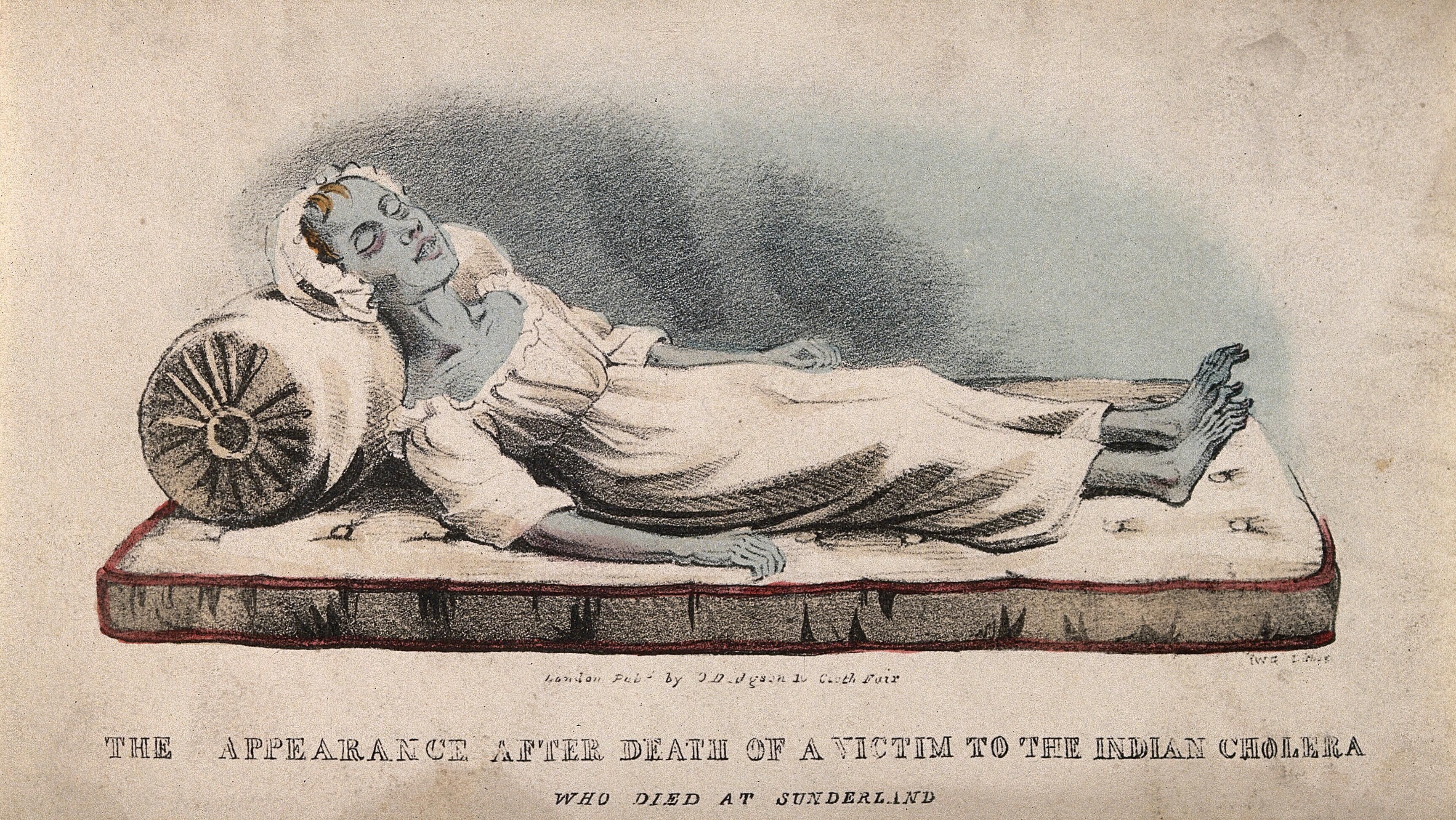

Cholera nostra, also known as English cholera or summer diarrhoea, included any acute intestinal disorder. It was a disease that mainly adversely affected the poor and malnourished citizens through dirty water and food. After the 1830s, the term virulent cholera morbus or Asiatic cholera was used, when it reached England as part of the first of six pandemics that occurred between 1816 and 1923. Transmission was attributed to the increase of commerce, migration and pilgrimage.

With the development of public–health policies, sanitation procedures and techniques, the 1848 Public Health Act began to address inadequate sanitation and to provide clean water supplies. However, suitable sewage collection and treatment systems were not implemented until London’s Great Stink of 1858, when hot weather intensified the smell of the untreated sewage and industrial effluent present on the banks of the River Thames.

The idea that microscopic organisms might have a role in human disease was old, but the evidence only evolved with the scientific study of microorganisms under the microscope during the 1670s. This evidence grew with the clinical experience of medical practitioners. Through observational studies on hand hygiene Hungarian physician Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis (1818–1865) pioneered antiseptic procedures in medical settings. Whilst religious handwashing rituals had been around for thousands of years, Semmelweis discovered that the spread of puerperal fever in labour wards drastically reduced when doctors washed their hands in a chloride solution.

By the late 19th century germ theory (diseases such as diphtheria, typhoid, cholera were caused by the invasion of the body by microorganisms) was advocated. This was credited mainly to the work of French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and German physician Robert Koch (1843–1910), commonly referred to as the fathers of bacteriology. Pasteur’s investigations revealed that fermentation and putrefaction caused disease, then proceeded to develop vaccines against anthrax and rabies. Koch and his associates discovered the causative bacteria of many diseases such as anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera.

As this latest pandemic infectious disease COVID–19 continues to test us, and we go through the stages of denial, anxiety, adjustment, re–evaluation and adjustment to the new norm, we wait for modern medicine to work on an effective vaccine. Collectively we are asked to modify our behaviour to protect ourselves and others, as the past has shown us that the health of the most vulnerable is a determining factor for the health of us all. As a precaution against the spread of this disease we do know what does help – isolating when required, physical distancing, wearing a mask in public and washing our hands with soap.

This article was originally published in fairhall, issue 30, March 2021, pp 22-24.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter