THE ART OF LIGHTING: ARTIFICIAL SUNSHINE

THE ART OF LIGHTING: ARTIFICIAL SUNSHINE

By Anne Glynn

THE ART OF LIGHTING: ARTIFICIAL SUNSHINE

In times past, lighting was regarded “as an expression of wealth and as significant as that indicated by furniture, paintings, silver, textiles and other precious objects … even in the homes of the rich, a spectacular display of illumination was reserved for those visitors who needed to be impressed, otherwise light was used sparingly.”

The earliest artificial lighting was made using a shell, a hollowed out rock or other naturally-found objects and later, pottery or terracotta dish or urn, filled with a combustible material such as dried grass and wood sprinkled with animal fat and ignited. To control the rate of burning a wick was added.

The main early form of domestic illumination was provided from the fire in the hearth and supplemented by rushlights, candles and oil lamps. In the 17th century, English hearth tax records show that 80% of houses had one fireplace, 14% had two and 6% had three or more. For those poor families living on subsistence wages, fats and oils needed for homemade candles or rushlights were expensive and too precious to spare often from their diet. The cheapest fats were thus used but were vile smelling. The cost of street lighting was reluctantly borne by the town citizens, so cheap fats and oils were also used there. Street lighting was thus extremely limited with the social consequence of increased night crime activity.

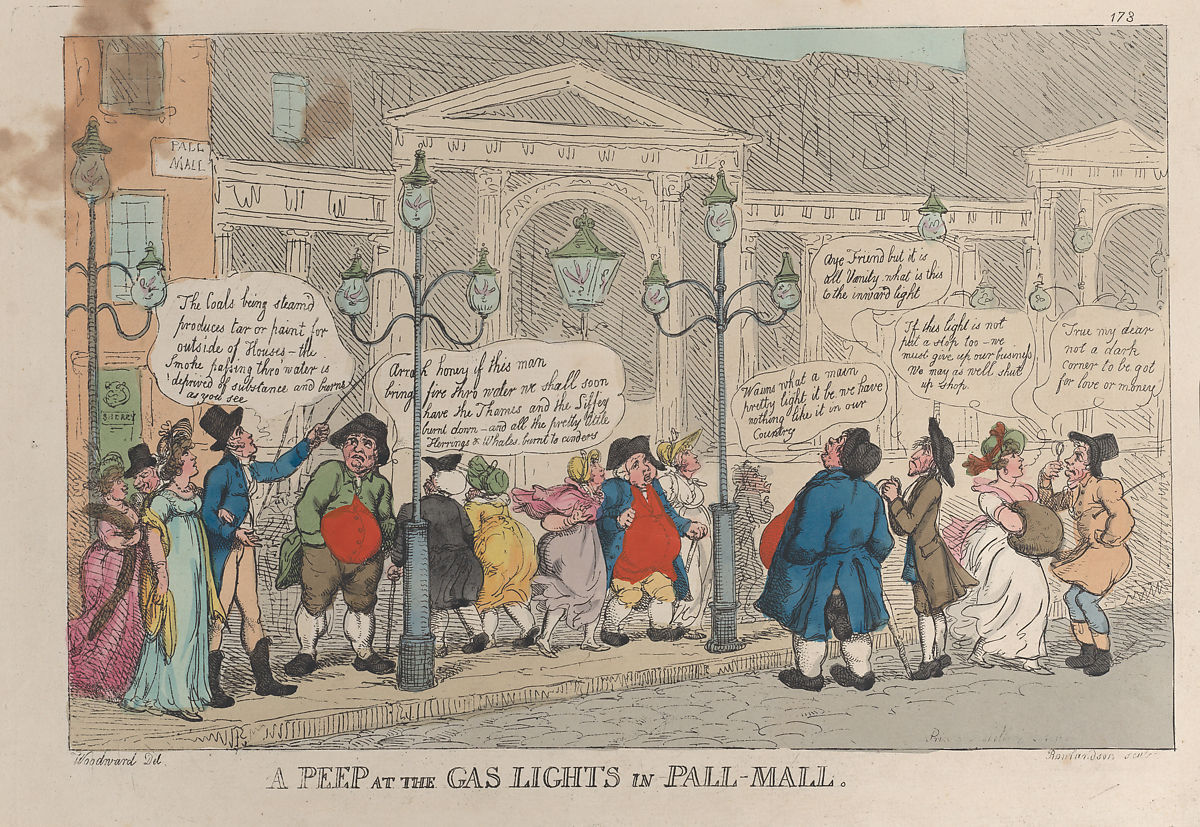

There was a demand for improved and efficient lighting so manufacturers and cottage workers could work throughout the night. This improvement was provided in the 1790s when Cornishman William Murdoch was able to exploit the flammability of coal gas and turn it into lighting. This revolutionised lighting in 1812 by firstly being used to provide efficient street lighting in larger towns and then in houses. By 1840 gas lighting grew in popularity and was eagerly adopted by the middle classes. The upper classes had reservations about the side effects of gas lighting - damage to light fittings and furniture, explosions and fires, but in the later decades of the 18th century, they adopted electric lighting enthusiastically. It was expensive, clean, relatively safe, healthier and convenient. A house lit by electricity was a luxury and indicated prosperity and progressiveness.

By 1920, good quality domestic lighting, whether gas or electricity, had become the norm in all houses for all classes of people and in the process, artificial lighting lost its significance as an indicator of wealth.

This article was first published in fairhall , Issue 13, November 14, pp 21.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter