THE ART OF LIGHTING: RUSHLIGHTS

THE ART OF LIGHTING: RUSHLIGHTS

By Anne Glynn

From the time of the Roman Conquest in Britain till the 19th century, rushlights have been used as additional illumination to the hearth fire, particularly for the poor.

Rushlights used in this form of lighting were easy to make and the rushes cheap to buy, with the added bonus that this lighting was not taxable. Two types of rushes were suitable, the common rush, Juncus conglomeratus and the soft rush, Juncus effusus, which grew almost everywhere. A pound and a half of rushes would supply a family all winter. There were approximately 1600 rushes to the pound and a good rush measured 2 feet 4½ inches long and would burn for nearly one hour.

Rushes were gathered while still green at the end of summer and usually picked by women and children. The rush had a soft white fibrous and absorbent pith, inside a tough green peel. Most of the peel was removed, except for a narrow strip, which kept the rush straight for ease in storage. The freshly gathered rushes were soaked in water to prevent them drying and shrinking, then left outside to bleach. They were then drawn through melted animal fat (tallow) or bacon fat, before finally being left outside again to dry on pieces of bark. Mutton fat dried hardest and was less messy, but bacon was a staple part of the diet for rural families, who may well have kept a pig, so was more readily available. The fat would have been collected over time in iron grease pans, which were then warmed at the fireside to re-liquify the grease. Rushes could be stored in bunches and hung from a wall holder by leather straps. This type of lighting was used not necessarily for reading, as many poor people were illiterate, but rather for illuminating craftwork that would be sold to supplement the family income. If additional light was required the rush could be lit at both ends, and it is from this practice that the saying “burning the candle at both ends” originated.

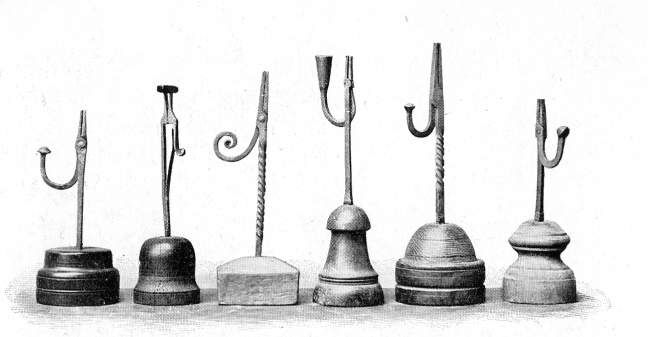

Rushlight holders stood either on the table, on the floor or suspended from beams. Iron rushlight holders had a spring to hold the rush firmly and would have been made by the local blacksmith. The very poor would hold the rush in a spiked block of wood. Floor length holders used more iron, could be height adjusted and decorated, so were more expensive.

There were several drawbacks associated with using rushlights, which minimised their use by the wealthy. Tallow had a terrible smell, like burning kitchen fat. The light produced was minimal and rags were needed under the rushlight holder, to catch any drips of grease. Despite this, rushlights were cheap and reliable especially for the lower classes.

This article was first published in fairhall , Issue 15, July 2015, pp 22.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter