THE LIBRARY

THE LIBRARY

By Helen Annett

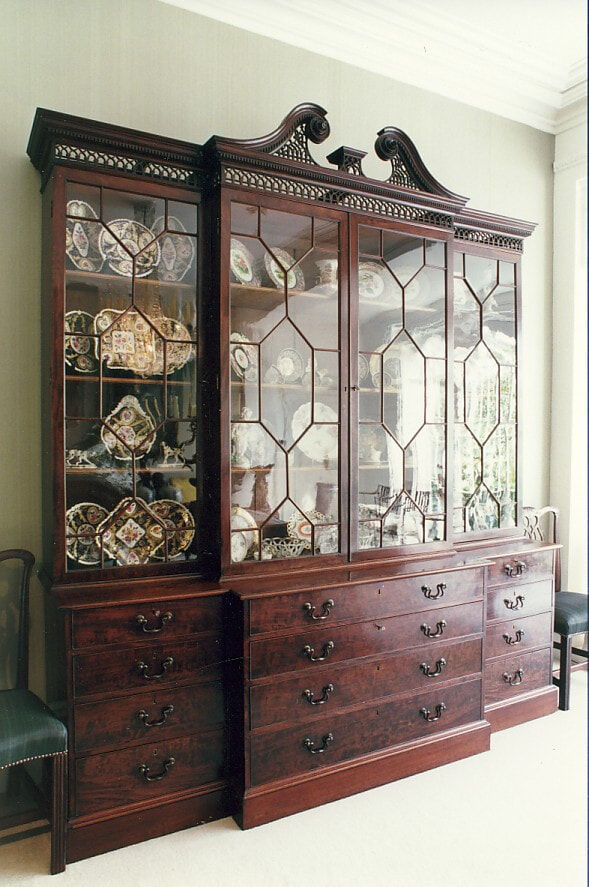

There are two Georgian breakfront bookcases in The Johnston Collection. Bookcases such as these were made for a specific purpose and setting: for the libraries of Georgian houses of the nobility and gentry. A better understanding of the pieces themselves is gained by considering the architectural context for which they were originally intended, and through tracing the development of the domestic library and its bookcase.

The 18th century was the heyday of the library as an integral, frequently used room in the house, especially in the country, and domestic bookcases developed concurrently. These country house libraries evolved from the earlier study or closet, which was a room containing shelves, storage for books, pictures and curiosities. This was an area for a gentleman to dedicate himself to private study. Richly bound volumes were a luxury and were stored in locked chests under desks, or in aumbries, wall cupboards, when not being read. Small hanging shelves were used for displaying books, and for exhibiting one’s wealth.

The route from monastic libraries and libraries of the Classical World to the domestic library is perhaps via collegiate libraries. Permanent libraries were established at universities in the Middle Ages.

In 13th century France, the Sorbonne University had designated book chambers, where books were either chained to desks or stored locked away in chests when not in use, presumably to prevent pilfering. When Lord Essex went to university at Trinity College Cambridge in 1577 his personal rooms also contained “a great desk of shelves for bokes [sic] in the study.”

Domestic bookcases and the emergence of the library in the country house date from the second half of the 17th century. During the reign of Charles II, the closet became the library.

Ham House has one of the oldest house libraries to survive. Here, the transformation from closet to library is evident, as the room is divided into two sections called the library, with presses for books, and the library-closet for pictures and objects of curiosity. On a less aristocratic scale, in 1666 Samuel Pepys began working with Simpson the joiner “with great pains contriving presses to put my books up in: they are now growing numerous, and lying one upon another on my chairs.” Clearly, something had to be done. Large bookcases made of oak-stained reddish brown were constructed for Pepys’ house near the Strand, and were later moved to his house in Clapham. There they were seen by the Bishop of Carlisle, together with models of ships, globes and with pictures and portraits of family and friends hung above them. Twelve of the bookcases are now in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College Cambridge.

With the influence of Palladianism in the early 18th century, due perhaps to the architectural background of William Kent, the architectural element of bookcases became more pronounced. The author and designer Batty Langley published guides for builders, carpenters and gardeners. He declared that bookcases were the province of architects and his Treasury of Designs of 1740 illustrates bookcases “true after any of the Five Orders”. However, Langley received complaints from cabinet makers that “’tis not possible to make cabinet-works look well that are proportioned by the Rules of Architecture.”

Around 1750 the formula of a bookcase with a central portion flanked by two recessed wings was established and the breakfront bookcase emerged. Even when the Rococo style was fashionable, the architectural breakfront shape was retained while assorted decorative motifs were applied somewhat like cake-icing, ranging from floral swags to eagle heads, and from pendants of fruit and flowers to dolphins.

In the 1762 edition of his Director, Chippendale comments on his designs for bookcases “the trusses, pilasters and drops of flowers are pretty ornaments … but all may be omitted if required.” From here onwards the classical revival encouraged restraint in ornament to allow the outline and form of the bookcase to take prominence, and to complement the Neoclassical decor of the room for which it was intended. For example, bookcases could be designed to fit purpose-built recesses in the library. A pair of pinewood bookcases painted white with gilt detailing were made for Sir Matthew Lamb to complement and flank the fireplace in the library at Brockett Hall around 1765.

And during all this, what was going on in the library? From the room for adult study the library had evolved into the hub of family life. Children had been let loose in the room. In Hogarth’s The Cholmondely Family in their Library (1732) the boys are running amok amongst the books. The Library became the Sitting Room for family and their guests, with an emphasis on comfort and comparative informality. Musical instruments could be brought into the room, as well as children. “You can’t imagine anything more cheerful than that room” wrote Lady Grey of her Library at Wrest in Bedfordshire in 1745. Could we perhaps call the Library the Family Room of the 18th century?

RECOMMENDED READING

Martin Wood, Nancy Lancaster, English Country House Style, 2005.

The book tells the story of Nancy Lancaster from her family home in Virginia to her adult years in England. She transformed the way people on both sides of the Atlantic decorated their houses and laid out their gardens. She bought out Sibyl Colefax in 1944 and went into partnership with John Fowler. This elegant book is richly illustrated with photos of the interiors of all the homes she lived in.

Mark Girouard, Elizabethan Architecture: Its Rise and Fall 1540-1640 , Yale University Press, 2009.

Anthony Fletcher, Growing up in England: the experience of Childhood 1600-1914, Yale University Press, 2010.

Adam Lewis, The Great Lady Decorators: The Women who invented Interior Design, 1870-1955, Rizzoli, 2010.

This article was originally published in Fairhall, Issue 2, April 2011, pp 10-11.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter