THE ART OF DINING: MIDDLE AGES

THE ART OF DINING: MIDDLE AGES

By Anne Glynn

These days we have a fascination with food and wine, reflected in events such as the annual Melbourne Food & Wine Festival. This series will look at the different styles of dining and their evolution over the centuries.

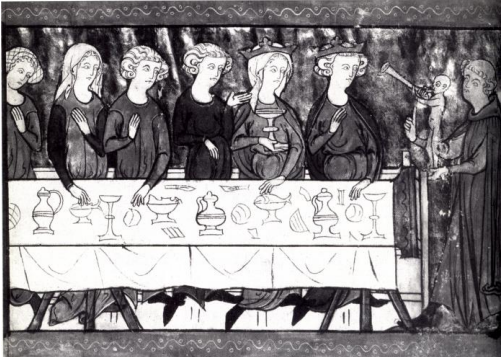

During the Middle Ages, dining was the great diversion of life, and your position at the meal determined your status and demonstrated the social hierarchy.

Feasts were as much about the display of wealth as they were about the appreciation of food. Silver was regarded as too expensive to be placed on the table and used, but rather was displayed on a court cupboard/buffet for all the guests to admire. The number of shelves that you were allowed on your cupboard determined your status. For example, ‘five shelves for a high-ranking duke, four for a lower duke, three for a nobleman, two for a knight and one for a mere gentleman’.

Dinner was held in the great hall and the guests sat at trestle tables along one side only. The food served depended on your position in society. ‘Fowl was never to be served to the humblest guests or to the servants’ ‘Lamb and fresh pork were also regarded as appropriate only for the higher classes, while beef and salt meat were good enough for the servants. Everyone however, had fresh vegetables’. The number of courses one received also showed your status. In 1517 a proclamation decreed that a Cardinal could have nine courses, six for a lord of Parliament and three for a citizen with a yearly income of £500.

In the 16th century there were two meals per day with dinner at 11am. Every meal began with hand washing and food came in procession. A well laid table would be covered with a number of (preferably) damask tablecloths, removed one by one as the meal progressed. Sometimes a leather sheet would be placed in between so as to prevent soiling the underlying tablecloths.

A large salt would be placed near the lord and most honoured guests, separating them from the others. Rank could be determined depending upon whether one sat ‘above or below the salt’. The drink also reinforced the status of the diners. White wine was considered suitable for ‘brainier upper classes while red was fit for labourers. Wine was served from the sideboard by the valet and the goblet was not placed on the table.

The carver served at the top table where the lord and special guests sat. His job was to carve the meat and slice the bread trencher for the medieval lord who was given the ‘upper crust’ only, instead of the hard bottom of the loaf. The remaining trencher was placed on a wooden square, where it prevented the meat juices from seeping through to the tablecloth. At the end of the meal the meat-infused bread was collected and distributed to the poor. The food on the other tables was placed on dishes in the centre of the table, from which one served oneself with one’s own knife and fingers. Spoons were only used for runny sauces and soup. There were no forks.

The quality of entertainment at a feast was important for the prestige of the host and was meant to impress his guests. It could be a spectacle such as a jousting tournament, merriment by court jesters and minstrels, or simply the ritual of serving and carving a piece-de-resistance for the main course. These could be watched by non-dining spectators.

References:

Masterpieces of Cutlery and the Art of Eating, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1979.

Roy Strong, Feast: A History of Grand Eating, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003 (p.82)

Margaret Visser, The Rituals of Dinner: The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities and Meaning of Table Manners, Penguin, 1992

This article was first published in fairhall , Issue 3, July 2011, pp 16.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter