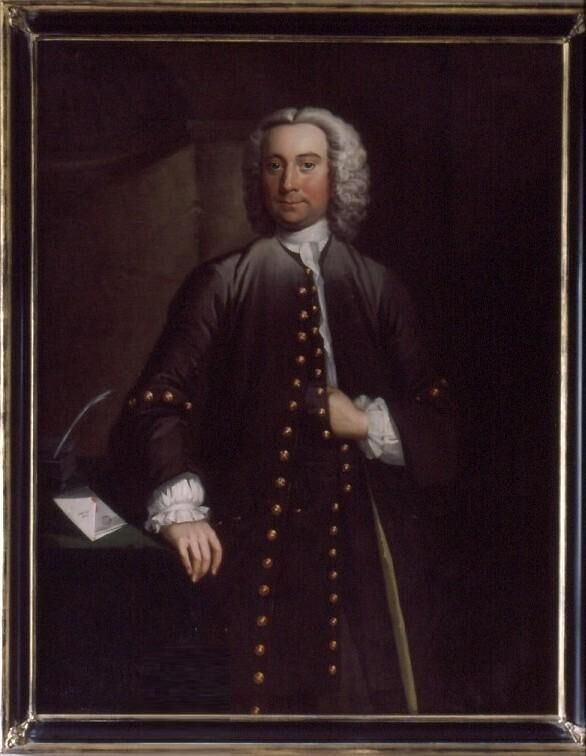

Portrait of a Gentleman

Portrait of a Gentleman

By Jan Heale

In England during the 18th century there was a greater demand for portraits than in any other country in Europe. Jonathan Richardson ‘the Elder’ (1665–1745) a portraitist and one of the most influential theorists of the 18th century, wrote in his Essay on the Theory of Painting (1715) that to ‘sit for one’s picture is to have an abstract of one’s life written and published and ourselves thus consigned to honour or infamy’.

The unknown Gentleman in this portrait is dressed in the fashion of the day, clad in a three piece suit with jacket, waistcoat and breeches of the same dark fabric. The generous cut of his silk lined coat, the many gold buttons, the fineness and whiteness of his linen, and the superior quality of his wig all indicate that he is a man of wealth. The marks on the letter at his right hand suggest that he is able to avail himself of free postage in the form of the ‘Franking Privilege’ which was a privilege largely limited to Members of Parliament and to Peers sitting in the House of Lords.

The subject adopts the hand-in waistcoat pose, a stance considered to be appropriate for gentlemen in polite society. It was highly popular in portraits, more so than in life. For portraitists it was a pose considered to be suitable to ‘persons of quality and worth’ who wished to appear agreeable and without affectation. In 18th century English portraits, the hand-in pose symbolised modesty and the rational style of rhetoric and typified the aristocratic British gentleman’s natural ease and eloquence, especially in contrast to the perceived volubility and flamboyant gestures of the French.

For the English upper classes a classical education included the study of sculptural models and familiarity with classical texts. Richardson’s Essay outlined portraiture’s ennobling aims and suggested ways in which the artist might be inventive. Of these, the ‘Airs’ and ‘Attitudes’ portrayed were considered to be the most important. ‘Air’ referred to the general appearance or manner of the person, generally using descriptions such as ‘lofty’ or ‘gay’. However, the ‘Attitude’ (or pose) was considered to be far more important in conveying character. Many of these were derived from classical sculpture. For example, the Apollo Belvedere’s ‘forward stride’, or the Leaning Satyr’s relaxed ‘cross-legged stance’. According to Richardson, ‘Antiquity’ provided an idealised antecedent that was borrowed by ‘all great poets and painters’.

In art, the figure of ‘Rhetoric’ is generally personified by an extended arm with open palm. However, the model orator of ancient Greece was expected to display extreme control and modesty before the Assembly, and especially to avoid any demonstrative gestures. The ‘hand-in’ attitude seen in 17th and 18th century portraiture has been linked to an ancient Hellenistic figure of the Greek statesman and orator Aeschines, and with John Bulwer’s 1645 canon for Rhetoricians which declared that ‘the hand restrained and held in is an indication of modesty’.

Over time the ‘hand-in’ stance elicited a different response. So prolific were portraits of Englishmen adopting this pose that it was caricatured by William Hogarth and others in their satirical images of ‘polite’ society. And when associated with images of Napoleon, it was perceived to represent arrogance and pride.

This article was originally published in Fairhall, Issue 6, July 2012, pp 17.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter