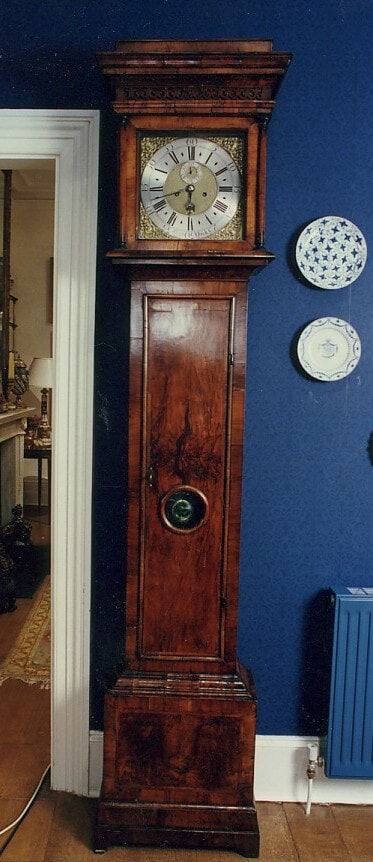

A longcase clock

A longcase clock

By Geoff Reid

The maker has signed his name - Hindley of York. Henry Hindley was a prominent provincial clockmaker who was born in 1701 and died in 1770. His working life was between 1731 and 1770. Henry Hindley was an inventor of note and perhaps was most famous for making a clock for York Minster.

The dial is square which had become universal by 1720. It is 11 ½ inches in diameter. Between 1700 and 1725 and later, clocks were usually between 7 and 8 feet 6 inches high and dials were 11 or 12 inches in diameter, just as this clock is. The spandrels consist of finely designed arabesques and contain a head with an exotic-looking headdress. The hands seem to be in keeping with the period and are probably original.

Inside the chapter ring there are four features: the seconds hand with its ring, the date aperture which shows the day of the month, 1 to 31, in Arabic numerals, and two holes for winding the clock - one for the clock mechanism, and one for the bell chime. You can see that in this clock these holes are covered. This is known as bolt and shutter maintaining power. Without maintaining power the clock stops while it is being wound and loses a minute or two. This is because the winding of the clock causes the weight to be removed.

The case is of mahogany veneer which is rare before 1750 but became almost universal, particularly in Lancashire and Yorkshire from 1760 onwards. There is crossbanding in another timber, but on the whole the case is fairly plain. The clock is 8 feet high. Earlier clocks, pre-1700, were about 6 feet high and the hood of the clock lifted upwards and is known as a rising hood. After 1700 this somewhat inconvenient arrangement was replaced by the sliding hood with a glass door in front of the dial to allow easy adjustment of the hands. This enabled the clocks to become taller. This one is 8 feet tall and therefore post¬1700. One sure way of telling an early pre-1700 clock is by examining the moulding under the hood ... If it is convex, the clock is pre-1700; if it is concave it is post-1700. This clock is concave of course.

The case has a flat-domed top with the later addition of two gilt balls. Whether the clock would have had these originally we do not know, but more important clocks between 1680 and 1725 often did. Notice the glass windows on either side of the hood. This was a feature of some seventeenth century clocks, and clearly was continued well into the 18th century. A decorative feature between the arched top and the dial is the delicately carved blind fretwork, a feature of the style sometimes known as Chinese Chippendale - you can see an example of open fretwork on the secretaire bookcase in the green room ... This style was in vogue circa 1770.

Interestingly, open fretwork, a 17th as well as an 18th century feature, had a practical as well as a decorative purpose - it provided the means for the sound to escape. It has been suggested, too, that the glass sides such as this clock has, were replacements for the original fretwork which had been broken.

Notice that the door of the clock contains a bull's-eye as decoration. Sometimes this is plain glass which enables you more easily to see the pendulum swinging. Some say this is to check that the clock is going, but this is unlikely because the loud ticking of these early movements will tell you that. It was more likely a little bit of snobbery - to show the world that you have one of the latest long pendulums.

Journals

About US

Explore

Contact

VISIT

See our VISIT page for hours and directions

BY PHONE

+61 3 9416 2515

BY POST

PO Box 79, East Melbourne VIC 8002

ONLINE

General enquiries

Membership enquiries

Shop

Donation enquiries

Subscribe to E-Newsletter